Scientific name: Vernonia missurica Raf.

Common name: Missouri ironweed

Plant family: Asteraceae

By Linda Churchill

Among the many attractive flowering plants of autumn, Missouri ironweed stands out. Intense purple flowers grace the top of this stately plant in late summer and early fall. The bright flowers and the plant’s strong presence are striking in combination with the season’s large grasses and golden sunflowers, and are a powerful backdrop to the transparent foliage and delicate flowers of other late blooming plants such as asters, agastaches and grasses.

Vernonia missurica. Photo by Steve R. Turner, Missouriplants.com

Many Vernonia species tend to be tall and stately, with sturdy but nonwoody stems; these strong stems are one possible reason for the common name ironweed. Missouri ironweed’s stems are typically downy with minute hairs. The simple, lance-shaped leaves are dark green and often have softly hairy undersides but can also be entirely smooth. The plant spreads primarily from its fibrous rhizomatous roots but also produces seeds that are generally wind-dispersed and will germinate further from the parent plant given suitable conditions.

The Vernonia genus is in the Asteraceae, or composite, family, but the Vernonia flower lacks the ray flowers typical of plants in this family; its flowers are made up of disc flowers only. The inflorescence (complete flower cluster) is at the top of the stem and may be several inches across, with 50 or more small disk florets in the capitulum (the compact flower head). Differences in the phyllaries, or flower bracts, are one means to identify various species. There are close to 1,000 species of Vernonia worldwide including several (17 to 25 depending on the source) in North America. Vernonia species hybridize readily, which may complicate species identification and make the exact species numbers difficult to quantify.

Vernonia missourica showing the capitulum and phyllaries. Photo: Richard Hawke.

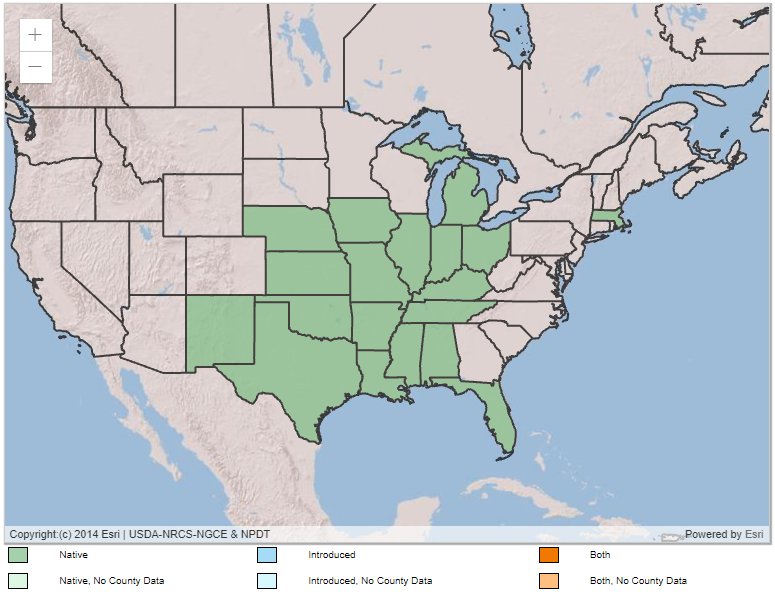

Missouri ironweed is native from southern Ontario south to Texas and Alabama. Some sources also list it in a few counties in New Mexico. Typically found in rich prairies and meadows, it also grows in more open areas such as along roadsides and railroad tracks. Ironweeds are not browsed by cattle and can be seen standing untouched in grazed pastures, which may account for the “weed” in the common name. But they are actually important native species and wonderful pollinator plants. Like all North American ironweeds, Missouri ironweed is visited by a wide variety of bees, butterflies, and other insects during its bloom period: “the sheer number and variety of insects drawn to their profuse display of late-season purple flowers is astonishing” (R. Hawke). The reddish-brown seed clusters, another likely explanation for “iron” in the common name, attract late-season songbirds.

USDA, NRCS. 2023. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 09/21/2023). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC USA.

Vernonias have not been used extensively in gardens but are gaining more popularity as interest in pollinator gardens has grown. Missouri ironweed may be more readily available in the Southwest than most other species of Vernonia. It is in fact an easy garden plant given full sun, adequate moisture and a bit of space.

Vernonia missurica in Santa Fe. Photo: Linda Churchill.

It is hardy in zones 4-9 and can be used to good effect in the colder microclimates of Santa Fe, where plants from warmer ecoregions can struggle through our mountain winters and cold springs. It is generally adaptable to most average garden conditions save very dry unirrigated soils. It can grow to 4-5’ by fall but the sturdy stems rarely need staking, making it an excellent back-of-the-border plant. Cutting stems back by 1/3 to 1/2 in early summer will result in a shorter plant that blooms 1 to 3 weeks later. It can also be grown in pots (this author has done so for several years), where the constrained root space keeps the plant shorter. Missouri ironweed can eventually spread or reseed happily in rich moist soil, but in New Mexico its growth is generally limited to irrigated gardens; the flowers need not be deadheaded here to avoid aggressive seeding. Our drier environment also reduces the likelihood of rust, one of the few problems in cultivation. The bitter leaves are generally not bothered by deer or rabbits, another boon to the natural gardener.

Photo: Linda Churchill.

Missouri Ironweed is long lived and eventually grows into a large clump with many brilliant flowers, but does not require regular division or extraordinary care to keep it healthy in the garden or landscape. It has beautiful winter presence even beyond the flowering stage, the dried flower heads on their sturdy stems gracefully catching frost and snowfall. It is so large by late summer that a massed planting may be overwhelming in all but the most naturalistic garden, but even one plant in the fall garden or landscape can be dazzling, a boon to pollinators and humans alike.

References

Hawke, Richard G., “Comparative Evaluation of Ironweeds (Vernonia spp.),” Plant Evaluation Notes Issue 45, 2020, Chicago Botanic Garden

https://www.chicagobotanic.org/sites/default/files/pdf/plantevaluation/no45_vernonia.pdf

Joseph Mooney, “Native Plant of the Week: Missouri Ironweed,” Matthaei Botanical Gardens and Nichols Arboretum, Aug 19, 2021

https://mbgna.umich.edu/native-plant-of-the-week-bottlebrush-buckeye-2/

Foster, Joe, “The Ultimate Guide to Ironweed – What you NEED to know,”

https://growitbuildit.com/ironweed-vernonia-grow-care-guide/#ID