Scientific name: Peraphyllum ramosissimum

Common name: wild crabapple

Family: Rosaceae (rose)

Article by Noah Gapsis, SFBG Horticulture Assistant

Before this summer, a widespread but seldom-seen wild crab apple was not to be found at our Garden; but, as of the end of September, we have three specimens – from different genetic sources – of Peraphyllum ramosissimum planted at SFBG. It’s time to shine a light on this tough but delicate, native crabapple.

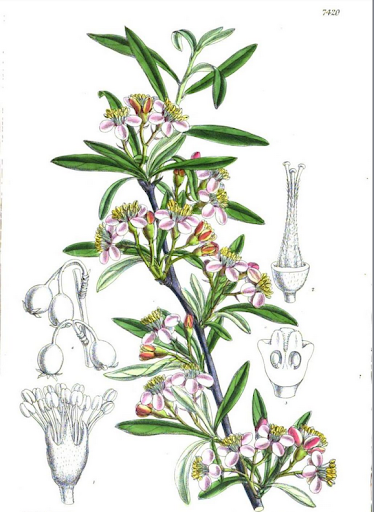

Left, illustration from Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, Vol. 121 By Sir WIlliam Jackson Hooker, 1895. Right, illustration by Majorie C Legitt, 2019 © Flora of North America Association.

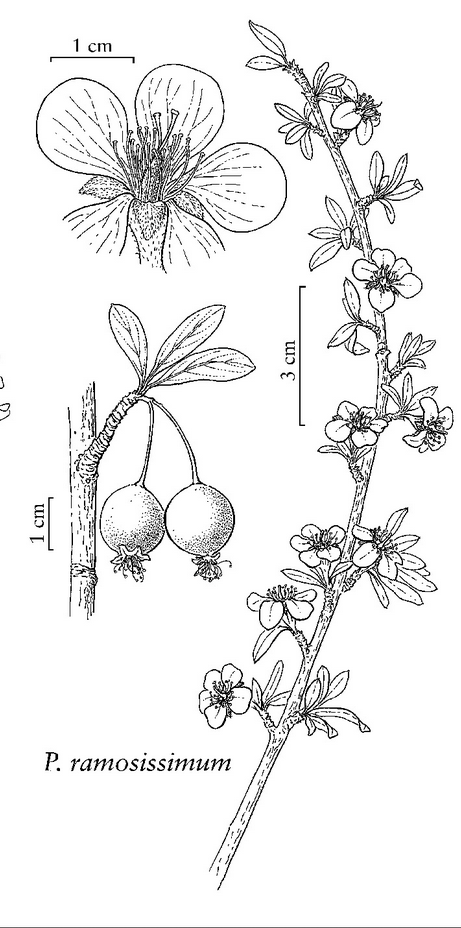

Peraphyllum is a monotypic genus in the rose family, containing the single species Peraphyllum ramosissimum, or wild crab apple. It is a deciduous shrub that grows in the dry openings or edges of the piñon-juniper, oak-sagebrush, and ponderosa pine communities. Endemic to the United States, it is fairly uncommon despite boasting a large native range. It is found in the mountains of eastern Oregon, California, and western Idaho, across the Nevadan great basin into the four corners area of Utah, western Colorado, and northern New Mexico, although conspicuously absent from Arizona.

Peraphyllum ramosissimum distribution. Natural Resources Conservation Service. PLANTS Database. United States Department of Agriculture. Accessed October 30, 2024, from https://plants.usda.gov.

From the Greek, Peraphyllum means “very leafy,” and the epithet ramosissimum refers to its “densely branched” growth form. In May and June, the thicketing, gray-brown branches are covered as densely with white to blush, radially symmetrical, perfect rose flowers, their unabashed stamens at attention. The rose-pink of unopened flower buds contrast the flurry of white flowers that are “scented of anise” (according to Robert Nold).

Photo © John Doyen, Calphotos

After pollination by a diversity of insects, small green apple-like pome fruits form, looking quite like serviceberries or crabapples as they ripen to yellow-red and orange-brown. A whole host of wildlife eat the fruits, including grouse and wild turkey, deer mice, chipmunks and ground squirrels, as well as American black bear and sometimes mule deer. The shrub with or without leaves makes great cover for passerine birds, which also undoubtedly delight in the fruits.

Photo Photo © David Burchfield, https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/167831550

Humans, of course, take an interest too. The fruits are quite sour when unripe; when fully ripe they are sweetish but with a bitter aftertaste and contain several large seeds. The fruits that fully ripen and then dry on the plant are the sweetest. Like gooseberries, they are suited to making jellies, although the best use might be in leaving them to to attract and sustain wildlife.

There is very little information about Indigenous uses of this plant in the literature. However, one doubts it would be neglected as a source of food, raw materials, and possibly medicine, especially with its wide distribution across the mountain west. For decades Peraphyllum was called “squaw apple,” and is often still listed with this common name in botanical literature today. The term squaw, understood to be derived from Algonquin and/or Iroquois words for woman, is a sexualized and racialized epithet used by European settlers and brought west with the doctrine of manifest destiny. The origin of the name squaw apple is unknown but one can imagine it being used as a racialized pejorative to describe the dryland shrub. Or, in a more generous reading, the name might refer to its common use by Indigenous peoples, likely women working to collect fruit and weaving materials. One report (a 1989 Department of Energy ethnobotanical review of the proposed Yucca Mountain Project site, oddly enough) states that Peraphyllum shoots and stems are used for baskets by the Paiute and Shoshone “much like” three leaf sumac, Rhus trilobata, which was also called “squawbrush.” These common names are likely a combination of both origins, a matrix of racist and observant neologisms by settlers to refer to and dismiss commonly used native plants.

And the wild crab apple does seem particularly useful. It thrives in bone dry clay, washes, and rocky hillsides, producing edible fruit and pliable stems for basketry. Its significance as a location to hunt grouse, wild turkey, and other wildlife, seems similarly notable.

Photo © Mark Wolter, https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/46853121

In our contemporary landscape in northern New Mexico, its tolerance of difficult sites and attractiveness to wildlife make for an appealing and underutilized native shrub. It would be at home in a naturalistic or wildlife garden, useful for erosion control and revegetation, and provides season-long charm in a tough spot. Watch the Garden’s new specimens grow near the David Salman tribute garden and along the approach to the Kearny’s Gap bridge.

References

Auger, Janene and Smith, Justin G. “Peraphyllum ramosissimum Nutt.” U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service. Retrieved from: https://www.fs.usda.gov/nsl/Wpsm/Peraphyllum.pdf

Bonner, Franklin T. and Karrfalt, Robert P. The Woody Plant Seed Manual. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, 2008.

Cooper, Janet G. Woody Plants of Utah: A Field Guide with Identification Keys to Native and Naturalized Trees, Shrubs, Cacti, and Vines. University of Colorado Press, 2011.

Fern, Ken. “Peraphyllum ramosissimum.” Temperate Plants Database. Web. Retrieved from: https://temperate.theferns.info/plant/Peraphyllum+ramosissimum. Accessed October 2024.

Gries, D. rev. Johnson, J. “Peraphyllum ramosissimum: Wild Crabapple.” NatureSere Explorer. Web. October 4, 2024. Retrieved from: https://explorer.natureserve.org/Taxon/ELEMENT_GLOBAL.2.143233/Peraphyllum_ramosissimum. Accessed October 2024.

Hooker, William Jackson. Curtis’s Botanical Magazine, Vol. 121. 1895. Web. Retrieved from:

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Curtis_s_Botanical_Magazine/_VFNAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0. Accessed October 2024.

Nold, Robert. High and Dry: Gardening with Cold-hardy Dryland Plants. Timber Press, 2008.

Potter, Daniel and Rosatti, Thomas J. “Peraphyllum ramosissimum.” Jepson eFlora. The Jepson Flora Project. Web. 2012. Retrieved from: https://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/eflora/eflora_display.php?name=Peraphyllum+ramosissimum. Accessed October 2024.

Schneider, Al. “Peraphyllum ramosissimum (Wild Crab Apple).” Southwest Colorado Wildflowers. Web. October 2024. Retrieved from: https://www.swcoloradowildflowers.com/White%20Enlarged%20Photo%20Pages/peraphyllum%20ramosissimum.htm

Stoffle, Richard W. et al. Native American Plant Resources in the Yucca Mountain Area, Nevada: Interim Report. Science Applications International Operation, 1989. Retrieved from: https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML0323/ML032390062.pdf