This month’s plant of the month article will introduce the newest part of Santa Fe Botanical Garden, the Piñon-Juniper Woodland, a characteristic community of two-needle piñon (Pinus edulis) and one-seed junipers (Juniperus monosperma).

The Piñon-Juniper Woodland at Santa Fe Botanical Garden

Article by Donita Frazier, DVM, PhD and Cristina Salvador, MS

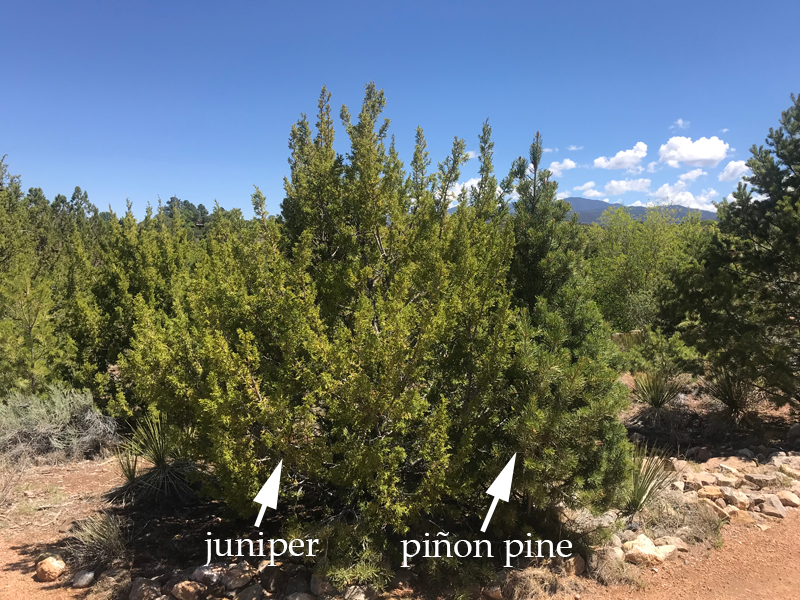

Have you ever wondered about the relationship between piñons and junipers? Have you contemplated how they always seem to grow intertwined, seemingly supporting one another? The newest part of Santa Fe Botanical Garden is now open for the public to experience while work and signage installation continues. This area will be left largely in its natural state, but this present state is not static. It is not what it always was or what it will likely become.

Photo: Andrea Neal.

The Pueblo people who occupied this land for thousands of years had no livestock. Cattle, sheep, goats, and horses were brought here by the Spanish. The mountains were primarily covered with conifer forests and the valleys and mesas were rich grasslands. Piñons and junipers occupied a relatively narrow transitional zone between the two – a zone that changed over the centuries. Santa Fe was established in 1610 in a grassy valley.

In the early years of the Spanish Empire, the Governor (acting with the King’s authority) granted large tracts of land to favored people, often conquistadors. Later, Spanish land use was built around the policies of granting tracts of land to groups of farmers and ranchers and designating common lands for grazing and wood gathering. By the time Mexico gained independence from Spain (1821), there were 62,000 sheep and goats and 1450 cattle in Santa Fe and its surroundings. The land was becoming overgrazed. The settlers led subsistence lives, with little contact with the outside world. The Spanish government prohibited trade with the American colonies and states, and it was not until the Mexicans gained independence from Spain in 1821 that trade was allowed. From 1821 until 1880, the area around Santa Fe Botanical Garden was part of a trade route that connected Independence, Missouri, with Santa Fe. This profitable endeavor was estimated at $5,000,000 (1.4 billion in 2018 dollars) in 1855. The fragile soil along the Santa Fe Trail became eroded by thousands of heavily loaded wagons, each carrying up to 6 tons of trade goods and pulled by teams of up to 12 or 16 mules or oxen. The Trail greatly decreased the isolation of Santa Fe. The town became a crossroads for traders that traveled south by the Camino Real to Chihuahua as well as west to California by way of the Old Spanish Trail. After New Mexico was seized by the United States in 1846, these Trails were used to transport mail as well as trade goods, as stagecoach lines, as routes for miners headed to the gold fields, and as immigration routes.

“Journey’s End” by sculptor Reynaldo Rivera displayed at entrance of Museum Hill on the Historic Santa Fe Trail.

In the late 1800s, the ancient pattern of small, frequent fires in this area was changed by erosion and overgrazing. After Anglo-American farmers and ranchers arrived via the Santa Fe Trail and railroads, livestock numbers skyrocketed. Open-range ranching increased as traditional Spanish land grants were broken up- some land was sold to speculators and unclaimed areas became Public Domain of the U. S. government. Confinement of Native Americans to reservations eliminated traditional burning practiced for hunting and agriculture. In addition, a primary mission of the U.S. Forestry Service, formed in the early 1900s, was to fight fires. These factors eliminated the grass, which is resistant to low-intensity fires and allowed brush to accumulate and tree seedlings and small saplings to grow. Those small fires, usually caused by lightning, had maintained the boundaries between piñon-juniper woodlands and adjacent grasslands. Bare land, land use changes and absence of fire, combined with intermittently wet periods at the end of the 1800s promoted the spread of piñons and junipers into the area that is now SFBG.

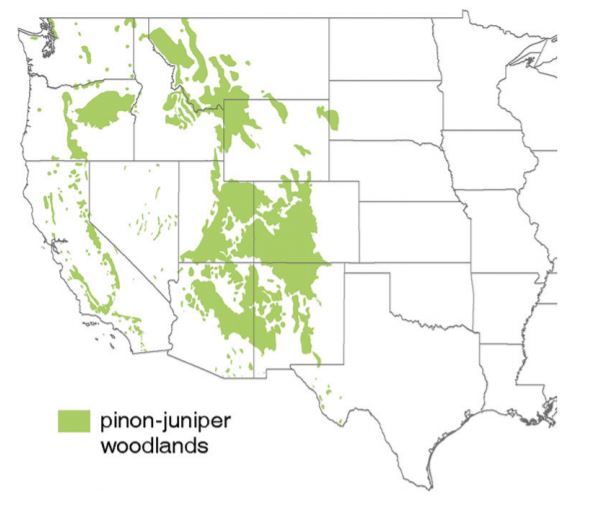

The Western United States Rangelands: A Major Resource, Figure 5-11.

Piñon-juniper woodlands cover over 100 million acres in 10 states and are the most common forest type in the Southwest. The particular piñon and juniper species in these woodlands depends on the prevalence of summer or winter moisture. From about 1350 to about 1850, the Northern Hemisphere underwent a change in climate characterized by very cold winters and exceptionally hot, dry summers, known as the Little Ice Age. Although tree ring analyses suggests New Mexico avoided consistently cold temperatures, contemporaneous writers indicated the Rio Grande and Santa Fe Rivers froze. Cold winters and hot, dry summers favor the growth of grasses over trees and shrubs. In the late 1800s, a time when overgrazing was widespread and fires began to be suppressed, the climate warmed and precipitation increased in many years. The piñon-juniper zone shifted to areas of lower elevation.

Piñon cone with seeds. Photo by Janice Tucker.

The newest part of Santa Fe Botanical Garden is a characteristic community of two-needle piñon (Pinus edulis) and one-seed junipers (Juniperus monosperma). Both trees are slow-growing, long-lived (up to 1000 years of age), and slow to reach maturity. Piñons may bear cones at 25 years, but good seed production does not occur until trees are 75-100 years old, and maximum production occurs at 160-200 years of age. Cones require 3 years to mature. Large seed crops are produced every 3 -7 years, depending on water availability, followed by multiple years of low cone production. One-seed junipers begin producing seeds at 10-30 years of age, with maximum production at 50-200 years of age. Fleshy cones, often called juniper berries, mature in 1 season, in late summer and autumn, and often persist on the tree for 1-2 years. Large seed crops are usually produced at 2-5-year intervals. Seeds of both species are dispersed by small mammals and birds, especially by scrub jays that cache large numbers of seeds. Seeds that have passed through the digestive tracts of birds and mammals germinate faster than uneaten seeds.

Scrub jay on juniper limb. Photo: Sonny Tucker.

Reproduction of the trees is usually sparse and scattered due to rapidly decreasing seed viability, consumption of most seeds by insects, birds and mammals, and difficulties of seedling establishment. Although both piñons and junipers are relatively intolerant of shade, their seedlings are best established in shade. The trees are often found growing together because each can act as a “nurse plant” to protect seedlings of the other from excessive drying and heating. Once established beyond the seedling stage, both piñons and junipers are very drought tolerant. However, one-seed juniper is more drought resistant and often grows at lower, drier elevations. Both species have tap roots and lateral root systems. Taproots of piñons may extend 20 feet or more deep. One-seed juniper taproots are often 12 or more feet in length, and have been reported as deep as 197 feet. For both trees, the shallow lateral root systems are concentrated in the top 6-12 inches of soil and often extend 2-3 times the distance of the crowns. Other adaptations for drought include retention of their needles for up to a decade.

Piñon-juniper woodlands can be classified according to stand structure as savannah, wooded shrubland or persistent woodland. Either piñons or junipers or both may dominate the canopy of all 3 types. Savannahs occur where summer monsoons predominate, supporting a low density of trees and shrubs, and a relatively continuous growth of grasses, forbs, and annuals. Wooded shrublands occur in areas having both summer and winter precipitation. These are areas of woodland expansion and contraction, shifting from dominance by grasses to shrubs to trees over time in the absence of fire. The trees range from very sparse to relatively dense. Persistent woodlands receive predominantly winter precipitation. This is a climax woodland where trees have predominated for several hundred years. Piñon-juniper woodlands are continually influenced by a complex interaction of natural disturbances and anthropogenic factors.

Prior to settlement, low-intensity surface fires caused by lightning at intervals of 10-50 years helped to maintain grasses and shrubs in the characteristic open stand structures of savannahs. Crown fires probably occurred in dense woodlands every 200-300 years. Both young and old piñon and juniper trees are very sensitive to fire because of thin bark (less than 1 inch), flammability of needles, and absence of self-pruning dead branches. Even low intensity fires may kill young trees or trees with low branches, particularly those less than 4 feet tall. Older, larger trees with thicker bark, junipers with high crowns that exceed flame lengths, and mature woodlands with little undergrowth may survive low intensity fires. Re-sprouting of fire-damaged junipers is rare and does not occur in piñons, so both species are usually killed by moderate to severe fires. After a fire, annuals and perennial grasses establish first, followed by shrubs. It takes 25 or more years for the trees to become established and 70-100 years for mature trees to suppress shrubs and become dominant. It can take 300 years for climax woodlands to develop.

Commonly occurring plants such as blue and sideoats grama grass (Bouteloua gracilis and B. curtipendula), big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata), rubber rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus nauseosus), cholla and prickly-pear (Opuntia spp.) are usually located in woodland openings and not directly under the trees. The extensive networks of taproots and surface roots are very efficient at extracting all available moisture. Understory vegetation is also limited by shading, competition for nutrients, and potential allelopathic effects. The trees concentrate organic material and nutrients (Na, Ca, Mg, K, nitrates, sulfates, phosphorus, and boron) beneath their canopies, creating “islands” of higher fertility over time. However, concentrations of phytotoxic organic salts may inhibit growth of some plants.

Opuntia sp. (Photo: Cristina Salvador)

Piñon-juniper woodlands comprise about half of New Mexico’s forests and have always been important to animals and humans. Piñon seeds and juniper berries are highly nutritious, providing proteins, unsaturated fats, vitamins, and minerals to birds and mammals, including humans.

One-seed juniper female “berries” (left) and male cones (right). Photos: Janice Tucker.

Although their needles are unpalatable to domestic cattle, sheep, and, horses, they are browsed to some extent by deer. Both trees provide cover for elk, mule deer, white-tailed deer, pronghorn, coyotes and many birds. The wood, bark and berries have been used for digging sticks, arrow shafts, weaving tools, house-building materials, food, medicine and as fuel for heating, cooking, and firing pottery for at least 10,000 years. They continue to be harvested and utilized today.

Fragile cryptogamic crust soils.

Piñon-juniper woodlands are fragile ecosystems and are particularly susceptible to anthropogenic changes. Heavy rainfall causes dramatic erosion when fire, livestock grazing, or drought reduces the amount of vegetative ground cover and organic litter. In healthy woodlands, biological soil crusts (communities of bacteria, cyanobacteria, lichens, mosses, algae, and/or fungi) reduce surface runoff and erosion, and enrich the soil by nitrogen fixation. Biological crusts are fragile and recover slowly when damaged by livestock, off-road vehicles, hikers, and bicycles. Piñons are particularly sensitive to severe drought conditions in the Southwest caused by climate change, becoming more susceptible to damage from several endemic insects, including bark beetles. Endemic beetle populations increase dramatically in woodlands of drought-stressed trees that are not able to repel them with increased resin production. Small insect populations cause isolated damage, but large insect populations also attack healthy trees.

Dead piñon pine. Photo: Cristina Salvador.

During the last 12,000 years, climate has fluctuated with periods of cooler or warmer and wetter or drier weather patterns compared to present patterns. There have also been variations in season of maximal precipitation. However, the rates of vegetation change during the last 120 years are unprecedented. A complex interaction between drought, insects, and disease is causing significant tree mortality in our woodlands. The changes due to anthropogenic factors are likely to continue. Summer rainfall is essential for seedling establishment and tree growth of two-needle piñons, and this tree is likely to decline if the monsoon season becomes less predictable. Our woodland is also dependent on winter precipitation, which has decreased in recent years. Decreased overall precipitation may lead to junipers becoming the dominant tree in our woodland. Alternatively, it could return to grassland. The association between piñons and junipers that you now witness in our woodland may be fleeting.

View overlooking Santa Fe Botanical Garden at Museum Hill. Photo: Andrea Neal.

Thank you to Sylvan Kaufman for proofing and editing this article.

References

Barrett, Elinore M. The Spanish Colonial Settlement Landscape of New Mexico: 1598-1680. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2012.

Dunmire, William. New Mexico’s Spanish Livestock Heritage: Four Centuries of Animals, Land, and People. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2013.

Gregg, Josiah. Commerce of the Prairies. The Journal of a Santa Fe Trader, 1831-1839. 2017 Edition (first published in 1844).

Havstad, Kris & Peters, Debra & Allen-Diaz, Barbara & Bartoiome, James & Bestelmeyer, Brandon & Briske, David & Brown, Joel & Brunson, Mark & Herrick, Jeffrey & Huntsinger, Lynn & Johnson, Patricia & Joyce, Linda & Pieper, Rex & Svejcar, Tony & Yao, Jin. (2009). The Western United States Rangelands: A Major Resource. 10.2134/2009.grassland.c5.

Renee A. O’Brien. New Mexico’s Forests, 2000 https://www.fs.fed.us/rm/ogden/pdfs/rmrs_rb003.pdf

USDA Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). Species: Pinus edulis

https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/pinedu/all.html

USDA Fire Effects Information System (FEIS). Species: Juniperus monosperma

https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/junmon/all.html

Official Data Foundation / Alioth LLC. 2019.