Scientific Name: Phoradendron juniperinum Engelm.

Common name: juniper mistletoe

Family: Santalaceae (sandalwoods)

Credit: Paul Asman and Jill Lenoble, Phoradendron juniperinum on juniper (Juniperus monosperma), upper Dale Ball trails, Santa Fe. Flicker (CC BY 2.0).

Article by Susan Bruneni

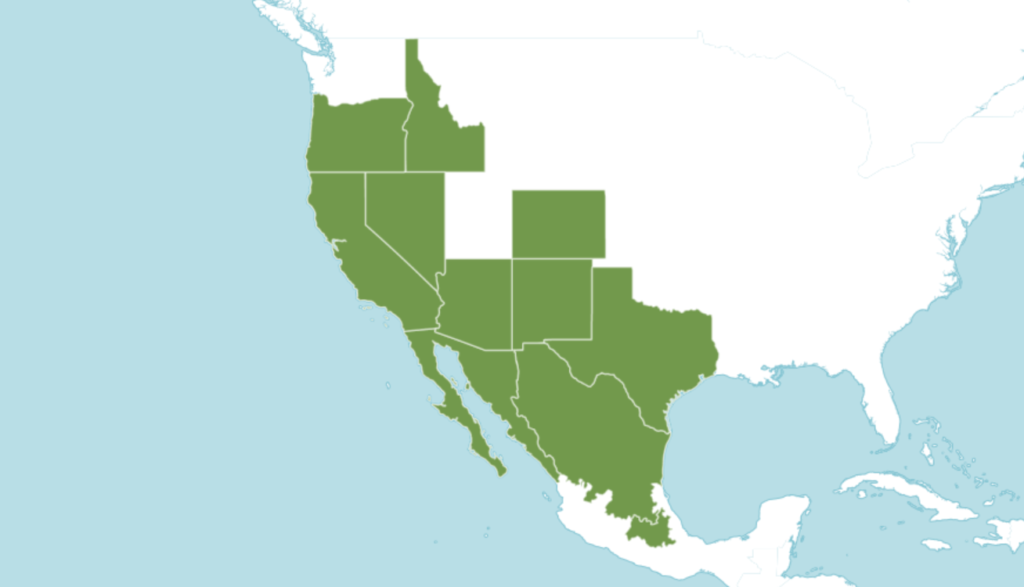

Juniper mistletoe (Phoradendron juniperinum) is a species of flowering plant in the sandalwood family (Santalaceae) and there are estimated between 1,300 to 1,500 mistletoe species worldwide. This species has adapted as a hemiparastic shrub specifically to juniper trees in the southwest United States (Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, California and Texas) and northern Mexico at elevations from 3,200-7,500 feet. The genus, Phoradendron, in Greek means “tree thief.” It is commonly found in juniper woodlands comprised of Utah juniper (Juniperus osteosperma), Rocky Mountain juniper (J. scopulorum), western juniper (J. occidentalis) or one-seed juniper (J. monosporum).

Native to: Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Mexico Central, Mexico Northeast, Mexico Northwest, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Texas. Map: POWO (2019). “Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/ Retrieved 29/01/2021.

The plant produces many erect and spreading yellow-green branches seven-eight inches long from a woody base where it attaches to its host tree, tapping the xylem for water and nutrients. It is hemiparasitic, meaning it contains chlorophyll and can photosynthesize some energy for itself. The smooth, noded branches have flattened, scale-like leaves.

Credit: Jim Morefield. Juniper mistletoe on Utah juniper (Juniperus osteosperma). Flickr, (CC BY-SA 2.0).

The plant is a dioecious perennial, with male and female individual plants producing different forms of knobby, greenish flower clusters. Female flowers yield shiny light pink spherical berries 0.15-inch wide.

Close up of berry. Photo credit: Janice Tucker

Birds eat the fruits and excrete the undigested seeds on tree branches, where they root. Fruit-eating birds distribute the seeds in their droppings or by wiping their beaks. Some bird species swallow the fruit whole and disperse the seeds to another tree, while other bird species pick out the seed, leaving it on the host plant, and swallow only the pulp.

When the seeds germinate, a modified root penetrates the bark of the host and forms a connection through which water and nutrients pass from the host to the mistletoe. It takes approximately two to three years for shoots to develop and another year before the plant produces berries.

Because it is hemiparasitic, juniper mistletoe generally will not cause sufficient damage to kill the host, unless there are additional environmental stressors. If there is a reason to remove the juniper mistletoe, cutting away the plant will not work. Removal of the entire branch is the only way to remove the roots that are growing within the host, which will send out new sprouts. Cutting away obvious mistletoe, however, may slow its growth, allowing the juniper host to recover slightly if you are also actively working to help the juniper to better health by watering and otherwise caring for it. Removing the mistletoe carefully and regularly may also reduce its ability to seed and thereby spread to other juniper trees.

The common Spanish name used by early settlers to describe juniper mistletoe was bellota de sabina, (bellota translating to “acorn” and sabina a common Spanish name for “juniper”) perhaps since the plant is found growing on the branches of the tree.

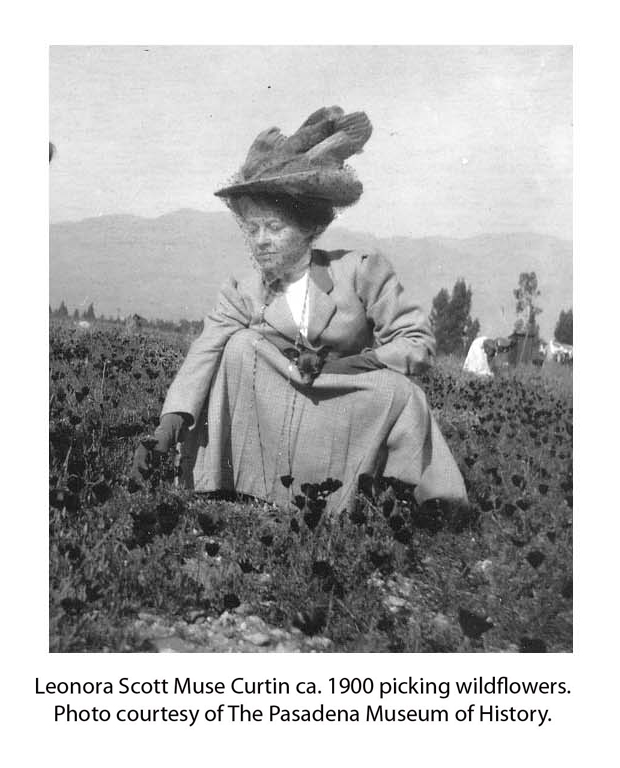

As related by Leonora Curtin in her book “Healing Herbs, Traditional Medicine of the Southwest” this name was also the name of a spell used to attach someone’s affections to another person. Leonora Curtin spent many hours strolling the roads southwest of Santa Fe, stopping to share knowledge about healing herbs and eager to learn about folklore, including magic spells.

Leonora Curtin wrote about numerous medicinal uses by Native Americans. However, there are other highly toxic mistletoe species in its growing range so extreme caution is necessary. But she makes it clear that “care should be taken because juniper mistletoe can have a variety of unpleasant side effects.” She continues, “I simply don’t understand the plant well enough to have any clear idea of its valid internal use.” For someone with her extensive knowledge of medicinal uses of plants, this is a valuable statement. She also cautions her readers not to confuse with similar more toxic species.

References:

Kinsey, T.B. “Phoradendron juniperinum – Juniper Mistletoe”. Southeastern Arizona Wildflower and Plants. Web. 17 Jan. 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.fireflyforest.com/flowers/2122/phoradendron-juniperinum-juniper-mistletoe/

“Phoradendron juniperinum”. Garden Explorer. Santa Fe Botanical Garden. Web. 30 Jan 2020. Accessed 30 Jan. 2020. Retrieved from: https://santafebotanicalgarden.gardenexplorer.org/taxon-558.aspx?qr=0

“Phoradendron juniperinum”. Wikipedia. Web. 29 July 2020. Accessed 17 Jan. 2021. Retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phoradendron_juniperinum

“Phoradendron juniperinum (juniper mistletoe)”. USDA, NRCS. 2021. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 30 January 2021). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

Shaw, D. “Getting to know mistletoe”. Growing Knowledge. Oregon State University. 2013. Pages 25-28.