Scientific classification (Division): Bryophyta

Common name: Mosses

Article by Susan Bruneni

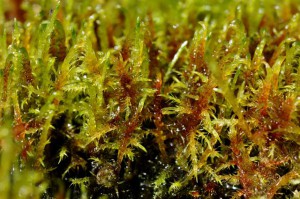

Scientific Name: Warnstorfia exannulata (Schimp.) Loeske

Photographer: Biopix: JC Schou.

Bryophyte, is the traditional name for any nonvascular seedless plant—namely, any of the mosses (division Bryophyta), hornworts (division Anthocerotophyta), and liverworts (division Marchantiophyta). Most bryophytes lack complex tissue organization, yet they show considerable diversity in form and ecology. They play a vital role in regulating ecosystems because they provide an important buffer system for other plants, which live alongside and benefit from the water and nutrients that bryophytes collect. Bryophytes represent the first adaptation of aquatic algae to life on land.

Mosses are small flowerless plants that typically grow in dense green clumps or mats, often in damp or shady locations. The individual plants are usually composed of simple leaves that are generally only one cell thick, attached to a stem that may be branched or unbranched and has only a limited role in conducting water and nutrients. Although some species have conducting tissues, these are generally poorly developed and structurally different from similar tissue found in vascular plants. Mosses do not have seeds and after fertilization develop sporophytes with unbranched stalks topped with single capsules containing spores. They are typically 0.2–10 cm (.07 – 4 inches) tall, though some species are much larger. Dawsonia, the tallest moss in the world, can grow to 60 cm (23 inches) in height.

In Gathering Moss, a Natural and Cultural History of Mosses (Oregon State University Press), author Robin Wall Kimmerer comments that “a true moss or bryophyte is the most primitive of land plants. Mosses are often described by what they lack, in comparison to the more familiar higher plants. They lack flowers, fruits, and seeds and have no roots. They have no vascular system, no xylem and phloem to conduct water internally. They are the most simple of plants, and in their simplicity, elegant. With just a few rudimentary components of stem and leaf, evolution has produced some 22,000 species of moss worldwide. Each one is a variation on a theme, a unique creation designed for success in tiny niches in virtually every ecosystem.”

In Gathering Moss, a Natural and Cultural History of Mosses (Oregon State University Press), author Robin Wall Kimmerer comments that “a true moss or bryophyte is the most primitive of land plants. Mosses are often described by what they lack, in comparison to the more familiar higher plants. They lack flowers, fruits, and seeds and have no roots. They have no vascular system, no xylem and phloem to conduct water internally. They are the most simple of plants, and in their simplicity, elegant. With just a few rudimentary components of stem and leaf, evolution has produced some 22,000 species of moss worldwide. Each one is a variation on a theme, a unique creation designed for success in tiny niches in virtually every ecosystem.”

Kimmerer’s book will be featured at the monthly meeting of the Botanical Book Club on Tuesday, February 13th, 1 pm to 2:30 pm. The club meets the second Tuesday of each month at the Small Udall Conference Room, 725 Camino Lejo. No RSVP is required.

Mosses are commercially available to highlight stone pavement, cover pots or stone walls, but their environment must be carefully monitored to insure adequate moisture. More than 343 species have been identified in New Mexico.

Photo courtesy of Dr. David Hanson. Syntrichia spp. (probably Syntrichia ruralis), which is often called star moss or twisted moss. It is very common in NM, often on trailsides and often looks like a palegreen or brown carpet. If you look closely, you see the beautiful star shape when they are wet and active. They can transition from dry to wet forms in seconds, going from completely dormant to fully active within 15 min.

The University of New Mexico (UNM) participates in several active research sites in New Mexico. A bryophyte inventory was conducted in the Valles Caldera National Preserve in New Mexico, from 2009 to 2011. Specimens representing 113 species of bryophytes were collected. Of those bryophytes, seven of the mosses were new to New Mexico: Atrichum tenellum, Dicranum tauricum, Orthotrichum pallens, Sphagnum girgensohnii, Tortella fragilis , Tortella tortuosa, and Warnstorfia exannulata.

According to Dr. David Hanson at UNM:

“This basal position among land plants makes them (bryophytes) an ideal group of organisms to study when examining the evolution of plants. Since they were the first plants to radiate onto land, comparing their physiological, structural, and developmental traits with those of green algae and other land plants helps elucidate the changes required for green organisms to transition from an aquatic environment to a terrestrial one. In my research on bryophytes, I try to find topics that either demonstrate some of the physiological adaptations needed for life on land, or other topics where bryophytes can provide unique insight into plant or algal physiology and/or ecology. “ For additional information, see Dr. Hanson’s Bryophyte page, www.unm.edu/~dthanson/bryophytes.htm

Photo courtesy of Dr. David Hanson. Syntrichia spp. (probably Syntrichia ruralis). It is very common in NM, often on trailsides and often looks like a palegreen or brown carpet.

Photo courtesy Dr. David Hanson. Syntrichia spp., brown twisted shape with the long thin white leaf tips very visible when dry.

Another informative source is the American Bryological and Lichenological Society.

Additional references:

Hanson, D. T and S. K. Rice (Eds.) 2014. Photosynthesis in Bryophytes and Early Land Plants. Vol. 37 in Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration, Govindjee and Sharkey (Ser. Eds.). Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. pp 342. ISBN 978-94-007-6987-8.

UNM: Museum of Southwestern Biology

Bryophyte Flora of North America

Key to the Moss Genera of North America North of Mexico, Dale H. Vitt and William R. Buck, University of Michigan Herbarium

Missouri Botanical Garden, mobot.org

www.efloras.org/florataxo

BioOne.org