Scientific name: Helenium autumnale L.

Common name: autumn sneezeweed, common sneezeweed

Family: Asteraceae

Suggested pronunciation: aster-A-cee-ee

Article by Janice Tucker

Note: Janice Tucker wrote this article on October 23, 2016, as a part of her “Wetland Wonders” weekly series for volunteers; however, it was never published for our general public audience. We’d like to share her unpublished articles with our readers as they are fun, informative and show Janice’s passion for all things botanical.

Helenium autumnale at Leonora Curtin Wetland Preserve. Photo by Kathy Haq.

Leonora Curtin Wetland Preserve (LCWP) will soon become still as it settles into the quieter time of winter. While we witness this season’s exit as it goes out in a blaze of glory let’s be thankful for the flora and fauna that flourished from May through October. Our deep appreciation of LCWP’s natural beauty is reaffirmed by these gifts of nature.

Scientific names: Genus – Helenium: Named for Helen of Troy. There is a bittersweet, mythical legend surrounding the Helenium genus. According to mythology, even to this day, the Helenium flowers spring forth from the spot where the beautiful Helen of Troy’s tears fell when she was abducted. Another version is that the flowers appear where she was collecting them when her captors seized her. Since this plant likes moist, or even wet soil, we can imagine the copious amount of tears shed by Helen as she was spirited away. However charming this myth may be, Helen could not have been everywhere these winsome flowers appear today. But it is a fun story to relate to LCWP visitors. Species – autumnale: Refers to autumn, the season in which it blooms. Carl Linnaeus named this plant in 1753.

Common names: western sneezeweed, common sneezeweed, autumn sneezeweed – It is obvious that “sneezeweed”, preceded by a variety of descriptive adjectives, is the most popular of the common names even though its uncomplimentary connotation certainly takes away from the beauty of this wildflower. “Sneezeweed” does not allude to wind-borne pollen. Its pollen is too heavy to be dispersed by brisk breezes and does not tend to pester our sinuses when the western sneezeweed is in bloom. The sneezeweed moniker actually refers to a snuff made from crushed dried leaves and seed heads of the plant. Bitterweed is also a common name that probably refers to its bitter taste. But you don’t want to taste it anyway. It’s poisonous. Helen’s flower: This common name reflects on the scientific genus of Helenium, named for Helen of Troy. What a lovely common name and certainly honors the attractive flowers much more than sneezeweed.

Helenium autumnale by bridge. Photo by Sylvan Kaufman.

The western sneezeweed patiently bides its time before bursting into bloom, taking over as the autumn floral displays of sunflowers and asters begin to wane. How clever of Mother Nature to stagger the blooming times in order to extend the pleasure of the fall season! This autumn flowering beauty is not usually recommended for gardens in Santa Fe’s dry climate. But the riparian plant zone at Leonora Curtin Wetland Preserve (LCWP) offers just the right environment for the western sneezeweed. During its brief blooming time the western sneezeweed (Helenium autumnale) usually shows its pretty self in sunny spots at LCWP on the northwest side of the Aster Bridge and the southeast side of the Viola Bridge. Sometimes it pops up near the picnic tables by the dock leading to the pond.

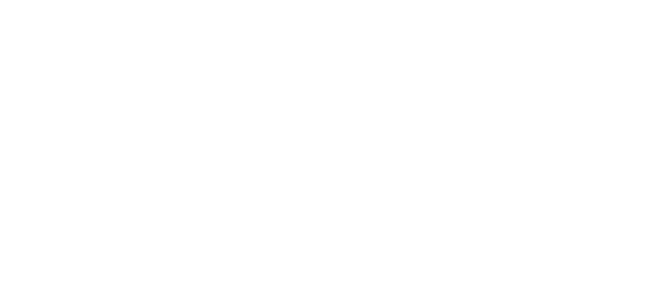

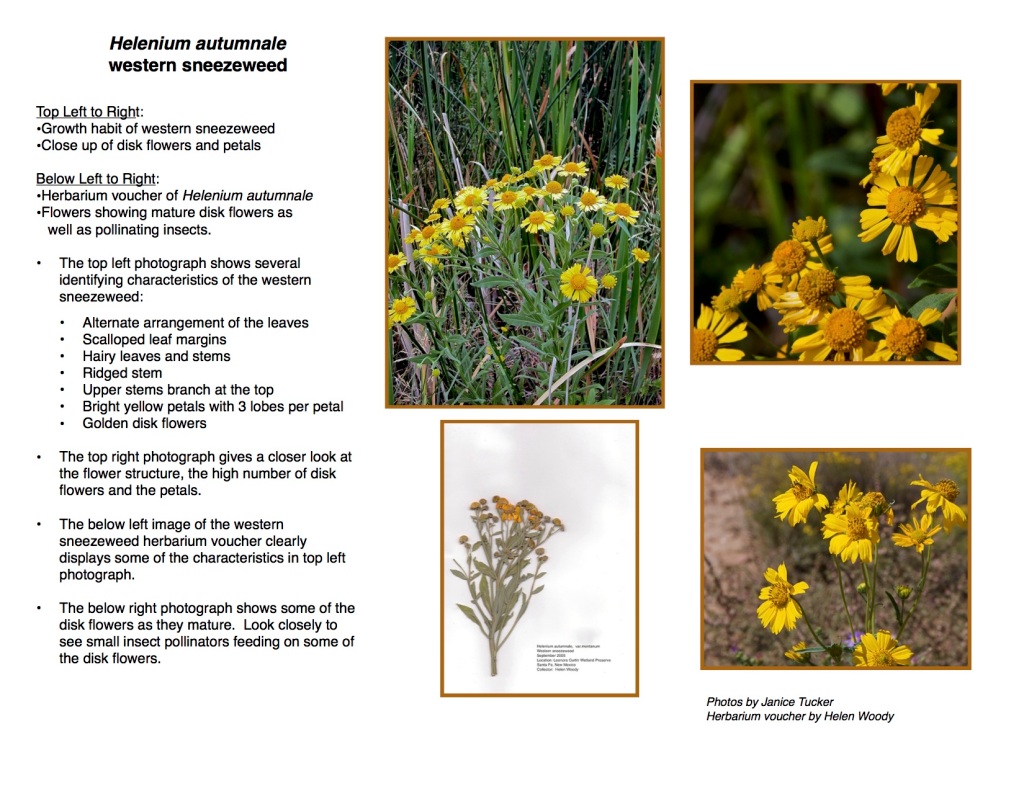

Rising up from shallow, fibrous roots in moist soil, the native, perennial western sneezeweed reaches a mature height of 4 to 5 feet. The lance-shaped, slightly scalloped, sessile* leaves alternately ascend hairy, ridged stems. The upper stems branch out to produce bouquets of brilliant yellow and gold flowers. Speaking of the flower, it emulates the image of the sun with 11 to 21, three-lobed, bright yellow petals radiating from a golden, domed center jammed-packed with fertile disk flowers. Even though there can be as many as 800 fertile disk flowers in an individual blossom, over-population of the species is avoided due to a low percentage of seed germination. Nature must have programmed the western sneezeweed to liberally pepper the soil with thousands of seeds in hopes that enough of them will sprout to ensure its continued existence.

The western sneezeweed is not pollinated by the wind, but by bees, butterflies and other winged insects. By fluttering its sunny yellow petals it blatantly flirts with pollinators, inviting them to come on over. Unable to resist, the insects yield to the temptation of sweet nectar and leave with a bit of pollen to deposit on the next flower they visit. Its pollen grains are too large to be tossed about in the wind and up an unsuspecting nose. This is where the common name of sneezeweed can be misleading. As was explained above, the significance of the common name, “sneezeweed”, refers to the intended sneeze reaction to the snuff made from its dried leaves and seed heads. So don’t blame the western sneezeweed for your sniffles unless you intentionally inhale a snootful of homemade-non-tobacco snuff concocted from sneezeweed.

Below are photos that will assist with learning identifying characteristics of the western sneezeweed:

Do evil sprits haunt you? Cancel the exorcist! According to some ancient folklore, a sniff of the snuff made from western sneezeweed resulting in an energetic AH-CHOO just might clear out those evil spirits. Uh huh…. On the downside, the western sneezeweed contains sesquiterpene lactones that can cause all sorts of mischief or worse. First and foremost you do not want to eat it since leaves, flowers and seeds are poisonous to humans, livestock (especially sheep), dogs and fish “when consumed in large quantities”. When a plant description is accompanied by a caveat that says, “poisonous when consumed in large quantities”, consider it as a warning that actually means, “DO NOT EAT THIS PLANT”! Ingesting it can result in any number of ills, some of them fatal. These components can also cause a skin rash. But those same elements are the western sneezeweed’s safeguard against plant diseases and herbivores. Don’t include it in your diet. It’s not on the food pyramid anyway. Leave those lactones to do their naturally designated job of defending the plant.

Since the western sneezeweed has a short blooming period its flowers may already be fading at LCWP. Perhaps we should emulate Helen of Troy by shedding some tears to ensure that the pretty yellow and gold flowers will reappear next year.

*Sessile means the leaves are directly attached to the stem – no petioles (short stalk) between a leaf and the stem).