Plant (Partner) of the Month: Ectomycorrhizal Fungi

A belowground partner essential to plant life

This month’s feature highlights not a plant, but the fungal symbionts that make many of our plants possible. Ectomycorrhizal fungi form intimate partnerships with tree roots, shaping forest health, nutrient cycling, and carbon storage.

Kingdom: Fungi

Major Lineages Represented: Basidiomycota, Ascomycota, Mucoromycotina (Ectomycorrhizae are not a single taxonomic group, but a functional category spanning multiple fungal lineages.)

Functional Group: Ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungi

Life Strategy: Symbiotic mutualists colonizing root tips of mostly perennial trees

Fruiting Body: Often mushrooms or truffle-like structures (the reproductive structures of the fungus; analogous to fruiting bodies in plants)

Plant Hosts: Species in the birch (Betulaceae), dipterocarp (Dipterocarpaceae), myrtle (Myrtaceae), beech (Fagaceae), willow (Salicaceae), pine (Pinaceae), and rose (Rosaceae) families

Distribution: Global; dominant in temperate and boreal forests, also present in tropical and Mediterranean systems

Why This Month Is Different

Unlike our typical Plant of the Month, which typically focuses on a single or related group of species, this feature centers on a symbiotic network. Ectomycorrhizal fungi are foundational ecological partners: they extend plant root systems through vast hyphal networks, increase nutrient and water acquisition, and facilitate inter-plant carbon transfer. By spotlighting ectomycorrhizal fungi, we broaden our understanding of plant conservation to include the unseen biological infrastructure belowground.

Author: Eva Maria Räpple

Winter in the Botanical Garden is a relatively quiet season when leaves have fallen to the ground and colorful blooming plants lie dormant. Instead of pink and yellow flowers the landscape is mostly shaped by contrasts of dark and light, and ice- and snow-covered grounds. But life continues, although less vibrantly than in the warmer months. Of course, there are birds and rabbits, deer and coyotes roaming and there are green trees that are not dormant throughout the winter. In the soil microbial life continues underground and fungi, these very important decay agents in the soil food web, work throughout the year. Certain fungi facilitate nutrient uptake through their mycelia (root like structure of mushrooms), which access organic and inorganic nutrients in the soil. These mycelia play a significant role in the decomposition of organic matter and the weathering of minerals, contributing to soil nutrient dynamics. Almost all terrestrial plant species form relationships between a fungus and the plant. Fungal hyphae that are interconnected with plants are called mycorrhizae (“myco”- “rhiza” meaning “fungus”-“root”). The article will describe a specific kind of mycorrhizae, ectomycorrhizal fungi (ancient Greek: ektós meaning “outside”), which are a fundamental phenomenon of nature and essential to forests and New Mexico’s pines.

As of today, about 144,000 species of organisms are classified as fungi but there are many more unknown species.[1] The word mushroom is likely derived from an old French word, mousseron, which means moss grower.[2] As quickly as mushrooms appear, for the most part during wet spells, they disappear again. A distinctive characteristic of ectomycorrhizal fungi is that their fruiting bodies are visible while the hyphae structures, the mycelia, are mostly underground. One gram of soil may contain about 60 miles of hyphae.[3] These hyphae can build enormous webs that also reach out to tree roots. More than 90% of vascular plants are linked with mycorrhizal fungi. In soils that lack the micro- and mycobiome of the forest, pine seedlings are very difficult or impossible to grow. It is essential to include organic material from forests to give pine seedlings a good start and increase their vitality. Small pine seedlings cannot survive in soils that for example have been heavily used and treated with pesticides, herbicides, fungicides.[4]

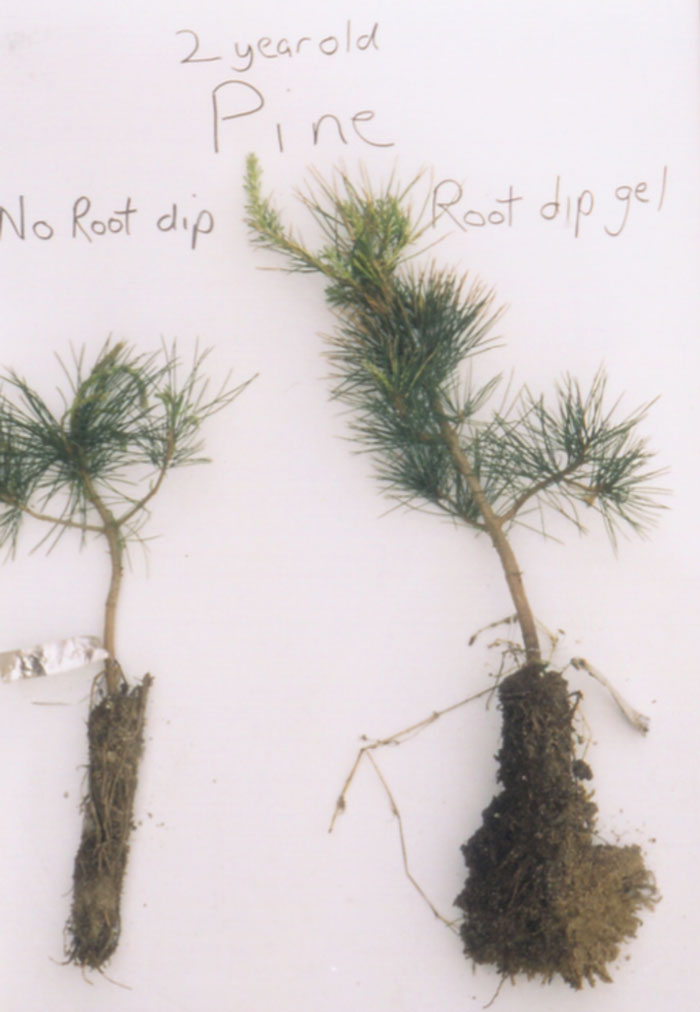

Below are examples of two-year growth in pine seedlings. The one on the right received a mycorrhizal fungi stimulant in form of a root dip gel.

Pine seedling without mycorrhizal fungi stimulant. Photo courtesy of Mycorrhizal Applications. https://mycorrhizae.com/

Pine seedling received a mycorrhizal fungi stimulant in form of a root dip gel. Photo courtesy of Mycorrhizal Applications. https://mycorrhizae.com/

Fungi like humid and wet forest floors and pine trees form an intricate symbiotic root relationship with mycorrhizae including some of the most well-known mushrooms. In New Mexico (and around the world) these include boletes, morels, puffballs, inkcaps, also agarics like the Amanita muscaria or fly agaric and the deadly destroying angel.

Amanita muscaria, fly agaric, fly Amanita. [5]

Amanita virosa, destroying angel. [6]

Amanita muscaria and Radiata pine ectomycorrhizae. [7]

Underground hyphal networks that trees rely on are of course not as easily examined as above ground structures. The first experiments were performed in the 1950 by two Swedish scientists Elias Melin (1889-1979) and Harald Nilsson (1921-1989) who grew pine seedlings in glass cups that contained bolete mycorrhizae and added radioactive compounds. Tests later showed radioactive phosphorus and minerals that had entered the pine shoots from the hyphal network. In return, the hyphae received sugars through the roots that the trees produced via photosynthesis, a beneficial exchange for trees and fungi. Moreover, hyphal networks and root connections share so called “signal molecules”. What the communication is about is not yet known but dangers such as insects or impending weather might perhaps be assumed as talk. [11]

Ectomycorrhizal fungi, these remarkable organisms, are only slowly receiving the recognition they deserve for their importance in soils, gardens, forests, life in general. Many of their fruiting bodies, though, have a long history of being valued among cooks and for medicinal properties. Today, awareness for the enormous contributions of ectomycorrhizal mushrooms to tree health are increasingly being understood and gain appreciation.

As a final note, there is a rapidly growing international effort to better understand and map these underground networks. The SPUN | Society for the Protection of Underground Networks is coordinating a worldwide initiative to map mycorrhizal fungal communities and advocate for the protection of belowground biodiversity. By integrating field sampling, genomic tools, and geospatial modeling, SPUN aims to make the invisible visible—bringing scientific and public attention to the vast mycorrhizal systems that underpin ecosystem resilience. [12] Their work underscores a central message of this article: conservation cannot stop at what we see aboveground. Protecting forests, grasslands, and rare plant communities also requires recognizing and safeguarding the fungal networks that sustain them.

“Mushrooms are a symbol of hope and renewal.” (Anonymous)

[1] “Fungus.” Encyclopaedia Britannica, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., [2025], www.britannica.com/science/fungus.

[2] Letcher Lyle, Katie. The Complete Guide to Edible Wild Plants, Mushrooms, Fruits, and Nuts: Finding, Identifying, and Cooking. Guide to Series, 2017. 50.

[3] Tim Crews. 2023. “To Regenerate, Look to the Ecosystems that Originally Generated” Resilience. Vol. 44, pp. 26-30.

[4] Dyshko, Valentyna, Dorota Hilszczańska, Kateryna Davydenko, Slavica Matić, W. Keith Moser, Piotr Borowik, and Tomasz Oszako. 2024. “An Overview of Mycorrhiza in Pines: Research, Species, and Applications” Plants 13, no. 4: 506. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13040506

[5] Amanita muscaria. Holger Krisp, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

[6] Amanita virosa, Destroying Angel.Ben DeRoy, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

[7] Amanita muscaria and Radiata pine ectomycorrhizae. Randy Molina, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

[8] Dyshko Valentyna.

[9] Lowenfels, Jeff and Wayne Lewis. Teaming with Microbes. Timber Press, 2010 (rev. ed.) 166-167.

[10] Dyshko Valentyna. 506.

[11] Seifert, Keith. The Hidden Kingdom of Fungi. Crestone Books. 2022. 66-67.

[12] SPUN | Society for the Protection of Underground Networks. (n.d.). Underground Mapping Project. Retrieved from http://www.spun.earth/underground